How might singing uniquely proclaim the Word?

This is the last installment of a three part series by Greg Cooper on the extent to which singing serves as an effective means of the proclamation of God’s Word.

Our last two posts have suggested that proclamation is crucial to Christian growth, and that as we seek to reach all aspects of our being (intellectual and emotional) with God’s Word, singing operates as a unique form of proclamation. But how does singing uniquely proclaim the Word? The way in which music impacts humans is, as you might suspect, a huge topic that is the subject of ongoing research.

So our suggestions here are introductory, but, we hope, pointing in the right direction.

Singing possesses distinctive qualities that may help the Word to dwell in us (as whole person beings) in unique ways. One such quality is singing’s ability to access and engage emotions. Bob Kauflin argues that “[v]ibrant singing enables us to combine truth about God seamlessly with passion for God. Doctrine and devotion. Mind and heart.”[1] He suggests that God “gave us music to serve the Word” – it is “a powerful gift from God that complements, supports, and deepens the impact of the words we sing.”[2] Indeed Paul writes to the Corinthian church of singing with both “my spirit” but also “my understanding”.[3] David Peterson suggests this “may…be a way of describing the participation of the whole person in the act of singing. Paul wants the Corinthians to… sing with mind and spirit together for the edification of the church.”[4]

Further, singing may enhance the meaning we take from words. As John Witvliet argues, “[music] is more than a shell for the text. The music we sing shapes the affections of our souls. It gives emotional content to the text. It interprets the text.”[5] If then, as we have suggested, there is importance in reaching both intellectual and emotional faculties through proclamation, song may have a unique role in achieving this.

Certainly, singing may be used unhelpfully to manipulate emotions. As John Calvin warned, “[w]e should be very careful that our ears be not more attentive to the melody than our minds to the spiritual meaning of the words.”[6] Kauflin contends, however, that “the problem is emotionalism, not emotions. Emotionalism pursues feelings as an end in themselves…with no regard for how that feeling is produced or its ultimate purpose.”[7] Such a warning calls for singing to be conceived as a Word-centred, Christ-focused activity, as commanded in Colossians 3:16. As Philip Percival writes, “[w]hat is important about our emotion is that it is inspired by the gospel.”[8]

Equally, however, if we are holistic beings, it seems possible to underplay the importance of emotions. In exploring how the gospel is communicated in worship patterns of the church (including singing), Bryan Chapell argues that worshiping God by acquiring knowledge of him may ensure “believers are consistently urged to worship in spirit and in truth” – but it can unhelpfully turn “the sanctuary into the lecture hall” and train believers “that right worship is simply about right thought.”[9]

Moreover, Jeremy Begbie argues that an emotion’s real force occurs when directed at an object – in our case, Christ.[10] As we focus on Christ as the object, Begbie suggests, we are reminded that Christ assumed all aspects of our humanness (including emotions) to redeem us – so “emotions are not intrinsically fallen or incidental to our humanness, but part of what God desires to transform.”[11]

Begbie also argues that emotions typically generate action. Hence, emotions “will likely have a key place in provoking the desire to do God’s will.”[12] This is of significance as we consider growing disciples of Christ in our churches. For action is a necessary component of discipleship. Indeed, Miroslav Volf contends that “[a]ction establishes conditions in which adoration of God surges out of the human heart… Without action in the world, the adoration of God is empty and hypocritical”.[13] A Christ-centred, Word-based approach to singing may therefore aid holistic Christian growth that leads to godly action.

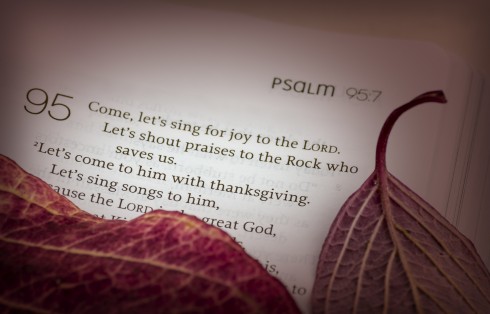

While song enables us to proclaim God’s Word, it also uniquely enables us to internalize and ‘own’ the words we sing. For we are not just hearing words proclaimed – we are proclaiming them, just as when stating a creed. This can be immensely beneficial in Christian growth. Writing of Israel’s songbook, the Psalms, Gordon Wenham points out that “singing or praying the psalms is a performative, typically a commissive, act: saying these solemn words to God alters one’s relationship in a way that mere listening does not.”[14]

What’s more, articulating song lyrics may also help identify sin. As David F. Ford and Daniel W. Hardy suggest, “[t]he simplest and healthiest way of identifying sin is by giving oneself to praising God and then following through the consequences into every area of life: does it all please God or does it make the praise hypocritical?”[15]

To this end, they argue, singing takes the crucial Christian medium of words and “takes them up into a transformed, heightened expression, yet without at all taking away their ordinary meaning.”[16] So internalising God’s Word through singing may help to set our hearts and minds on things above,[17] while also helping us rightly assess the godliness of our lives. Witvliet paints a picture of music as “soul food” that “once ingested becomes indistinguishable from us. It is something that is identity shaping, soul forming, and spiritually nourishing.“[18]

That singing is a form of identity shaping is significant in the Christian transformation process. For as James K.A. Smith argues, church worship practices shape our identities by shaping what we love. For Smith, singing’s engagement of the whole person – mind, emotions, and body – grants song a “privileged channel to our imagination”, making it “a primary means for reordering our desires”.[19] Songs are “compacted theology”, Smith suggests – so “what we sing says something significant about who we are – and whose we are.”[20] Singing is therefore an important way of restating and re-owning our identity, and illuminating areas of life in which we may seek transformation by the Spirit.

Recently I attended a conference that addressed the intersection of Christian faith and politics. During one of the talks, a protester unexpectedly appeared from within the crowd of 600 delegates, and started verbally attacking the speaker. As we all looked on in shock, and as security guards made their way towards this protester, a lone delegate started singing these words:

“Amazing grace, how sweet the sound, that saved a wretch like me…”

In this emotionally-charged environment, these words and their melody cut through the nervous silence like a balm to our souls. Almost instantly, the whole room joined together in song, and sang the first verse of Newton’s famous hymn.

Just like Jesus fought Satan in the desert with God’s word, so we were fighting opposition to the gospel with God’s word – through song. And just as Paul called the Ephesians to be filled with the Spirit by singing, so we could sense the Spirit’s peace upon us as we sang. It was palpable. This was proclamation in action – not merely for intellectual strength, but for emotional comfort, and corporate edification.

We have suggested that singing in our church gatherings operates as a unique form of proclamation of the Word. In particular, singing’s distinctive qualities may allow transformation to occur in unique ways, as the Spirit transforms our minds and hearts to full maturity in Christ. Proclamation of all kinds is central in this transformation process – and singing may have a unique proclamation role, especially when our nature as both emotional and intellectual creatures is considered. In particular, an exploration of key verses in Colossians and Ephesians suggests that singing allows the Word to dwell richly in us, and therefore to fill us with the Spirit and his wisdom.

Indeed, singing’s engagement of our emotions and its ability to generate self-assessment may mean it uniquely serves Christian transformation through the Word, by the Spirit.

[1] Kauflin, True Worshippers, 108; emphasis added.

[2] B. Kauflin, ‘What happens when we sing?’ in J. Piper and J. Taylor, The Power of Words and the Wonder of God (Illinois: Crossway, 2009), 124; emphasis added.

[3] 1 Corinthians 14:15b.

[4] D.G. Peterson, Encountering God Together (Nottingham: Inter-Varsity Press, 2013), 134-5.

[5] J. Witvliet, Worship Seeking Understanding (Ada: Baker Books, 2003), 237; emphasis added.

[6] J.T. McNeill, ed. Calvin: Institutes of the Christian Religion – Volume 2 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1960), 895.

[7] B. Kauflin, Worship Matters (Illinois: Crossway, 2008), 99; emphasis added.

[8] P. Percival, Then Sings My Soul, (Sydney: Matthias Media, 2015), 106.

[9] B. Chapell, Christ-Centered Worship (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009), 67; emphasis added.

[10] J. Begbie, ‘Faithful Feelings’ in Resonant Witness, 338.

[11] Begbie, ‘Faithful Feelings’, 337.

[12] Begbie, ‘Faithful Feelings’, 337.

[13] M. Volf, ‘Worship as Adoration and Action: Reflections on a Christian Way of Being-in-the World’ in D.A. Carson, ed. Worship: Adoration and Action (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 1993), 211.

[14] G. Wenham, The Psalter Reclaimed (Illinois: Crossway, 2013), 34.

[15] D.F. Ford and D.W. Hardy, Living In Praise (London: Darton, Longman and Todd, 2005), 20.

[16] Ford and Hardy, Living In Praise, 19.

[17] Colossians 3:1-2.

[18] Witvliet, Worship Seeking Understanding, 234.

[19] J.K.A Smith, Desiring The Kingdom (Ada: Baker Publishing Group, 2009), 170-1.

[20] Smith, Desiring The Kingdom, 172.

- Greg Cooper currently works part time with Effective Ministry, researching the place and importance of music in disciple-making. He is also Creative Director of EMU Music.